Field Work in Mozambique, June 2023

Published:

There’s a first time for everything…

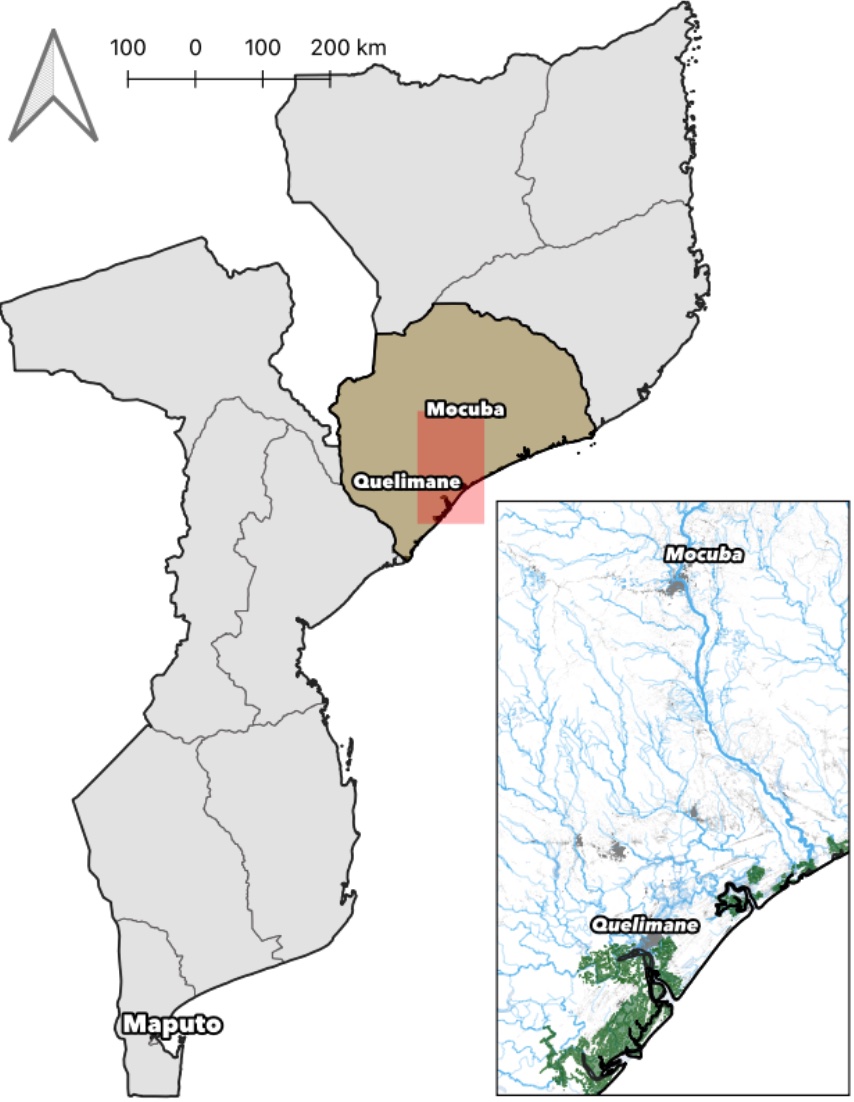

Five years ago if you had told me I’d be in Mozambique doing field work on urban flood risks and erosion hazards I wouldn’t have believed it. But here we were hiking up the Licungo river basin near the city of Mocuba, late June when the sunny sky was aqua blue.

Our visit started in Quelimane, capital of the Zambezia province and a city at the nexus of multiple waterways and the coast. Situated on the Cuácua River (Rio dos Bons Sinais) about 25 km inland from the Indian Ocean, the whole city is often at risk during the cyclone season. Most recently by cyclone Freddy in March 2023 which made landfall in Quelimane and from which the city is still rebuilding. Mangrove fields hugging the coastline are one of the main lines of (natural) defence to protect residents and the built environment against tidal surges and storm damage. Inland, riparian floods can cause significant damages at the confluence of different drainage basins during rainy periods.

The work? An interdisciplinary, international and community-engaging research project coming from all our shared experience at Nova School of Business and Economics and funded through the International Growth Centre (IGC). Myself, Stefan Leefers, Pedro Vicente and Patricia Caetano all with ties to Nova - Stefan and I as former PhD students now lecturers in the UK, Pedro as professor and director of Novafrica, and Patricia coming out of writing her dissertation to take on our project and field work coordination and bringing in a wealth of experience managing previous projects in the area. Although this was my first time there, between the rest of the team there was a collective experience of years working on economic development research with partners across Mozambique.

Our broad project aim is to study at-risk areas where we have the intersection of population growth, land use pressures and water hazards (flooding, erosion). Our initial visit helped us to understand what feasible and efficient urban interventions (e.g. drainage, building and land use choices, informal constructions, mangrove protections) and community-led initiatives could be successfully promoted to allow local areas to build resilience against increasing threats of flooding and impacts of climate change.

Data science and open GIS data work (e.g. WorldPop, Google Earth Engine, Sepal.io, Planet) allowed us to identify target areas of interest to visit beforehand, which we validated on site with local resident experts. What caught me the most was the vast potential (and limitations) of finding different open source datasets to better understand the local environment, landscape and challenges. But also, it is crucially important to think in detail about what pre packaged datasets, indicators, aggregations or reported values actually represent in situ. Even the highest of data resolutions and most frequent collection mechanisms can only tell us so much of the story without considering the real local dimension of the nature and people on the ground. Biases around who collects, uses, has access to and is actually represented in each of the data must also always be considered. While open source remote sensing land use data goes a long way towards mitigating some of these biases, all data analysis should be accompanied by a critical reflection on the source inputs and methods.

In Quelimane we met with and presented some work to local officials including Mayor Manuel de Araujo, a champion for positive urban regeneration in the city. He held a palestra (town hall seminar) at the local câmara municipal for workers and the public (and well attended live streamed!) for my project partners to describe outputs from Novafrica’s previous projects and for us to introduce the current team and our ongoing work. Follow up meetings and discussions were very useful to learn best practices, where we can support ongoing work, and to make sure our research aligns with realities on the ground.

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=787432366201149

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=787432366201149

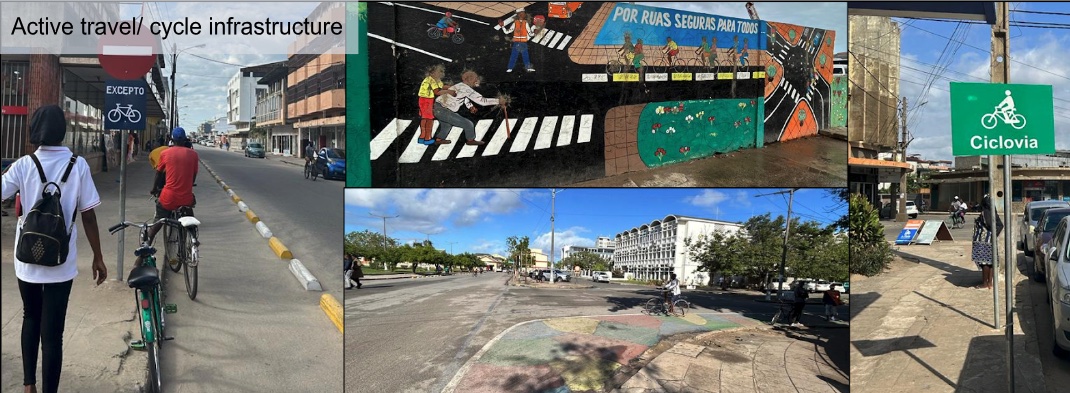

Quelimane was lovely, in the peak of their winter season. With peri-peri chicken, prawns, freshly caught fish, xima, matapa and mucapata on the menu, there was never a scarcity of choice for delicious food. One thing which struck me about the city was the scale of active travel adoption, with almost everyone cycling and much fewer cars (even bicycle taxis!). The city centre had dedicated biking infrastructure and colourful urban interventions, and this was said to be a key priority area for the municipality. Having a Dutch research partner beside me on the cycle filled streets of Quelimane, I could have easily thought I was out on our annual USP Level 3 field trip to Rotterdam (though slightly nicer weather).

A pre-sunrise departure brought us inland to Mocuba where we saw different types of flooding impacts, having experienced significant damages and flooding in 2015. Ultimately there was a planning success story with local policy and enforcement measures managing to stop the reconstruction of more informal residences in these risky areas post-flooding. Residents were incentivized to move to new development areas away from immediate risk. The Licungo river margin around Mocuba is no longer dotted with dwellings at risk anytime there are high water events, but is now mainly for leisure, commerce and domestic uses.

After making sure Patricia was settled in for her field work coordination in Quelimane over the next few months, the rest of us spent the last days of the visit in the capital city of Maputo. Here, the local IGC team was great in helping to coordinate meetings and discussions with relevant research and policy stakeholders. A caipirinha on the last evening there while seated overlooking the relatively new Maputo-Katembe bridge spanning Maputo Bay was a perfect cap-off to the experience.

Foi uma experiência maravilhosa e profundamente importante para a análise de dados que vai seguir. Research collaborations can lead you to great places and great outcomes.

Jacob L. Macdonald